Hello, I’m Cheri and I am a linen addict. I’ve been trying to get better, but it’s so hard. I Marie Kondo’d my linens and gave away a bunch of stuff, but there still seem to be lace, damask and cotton pouring out of the cupboards and closets. If you read my post on doilies, you probably already assumed this. So that this obsession feels a little less obsessional, I’m going to do some more posts on all the cloth bits and bobs. That way, “I’m not hoarding, I’m researching.”

As with most things etiquette and table related, the beginnings of the napkin are murky.

“Use of the napkin first became ordinary in northern countries in the 17th century. The idea came from Southern Europe. In the middle of the 16th century the napkin was used in Europe and Scotland and in the Scandinavian countries. Before this time it was perfectly good manner to wipe your mouth on the table cloth or with your hands.”

The Noble Art of Setting the Table by Royal Copenhagen Porcelain and Georg Jensen Co., 1977

“It is a matter of regret that table napkins are not considered indispensable in England; for, with all our boasted refinement, they are far from being general. The comfort of napkins at dinner is too obvious to require comment, whilst the expense can hardly be urged as an objection. If there be not any napkins, a man has no alternative but to use the table-cloth, unless (as many do) he prefer his pocket handkerchief – a usage sufficiently disagreeable.”

The Book of Fashion and True Politeness or the American Hand Book of Etiquette by Charles William Day (1856)

It is wonderful to note that napkins were not ubiquitous at this time in Britain. It paints a vivid picture of how dinner tables really might have looked. Now, the idea that people wiped their mouths on their host’s tablecloth isn’t really accepted anymore and it’s likely that Charles was indulging in a bit of hyperbole. It is unlikely that anyone appreciated a guest putting grease on their expensive tablecloth, especially at a time where very few people owned fine tablecloths at all. Like with costume history, the history of etiquette and protocol is riddled with inaccuracies and apocryphal stories. It’s only recently that these topic are being given respectful consideration in an academic sense. For years one had to guesstimate from paintings or literature to figure out the history of these items and how they were used.

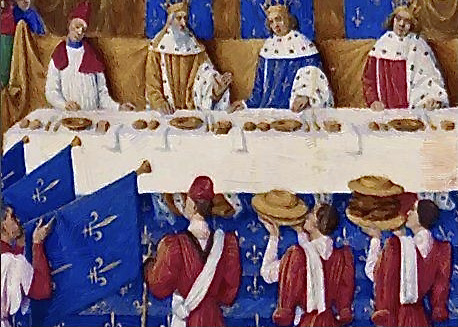

Hold onto your hats, I’m about to get woefully general here. I’m going to glance at antiquity and then head straight to the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages lasted from the 5th century to the 15th century and was a time of radical change to society and etiquette dictated by the Crusades, exploration, religious upheaval, the spice trade, and more. I’m starting here because this is when you see evidence of napkins in art and indeed, napkins seem to have become a more commonly used table linen somewhere during this lengthy period. Just remember that we’re talking about 10 centuries, so when I talk about the Middle Ages, whatever I discuss won’t be true of all of the Middle Ages. Please, bear with me.

While tablecloths, (also referred to as board-cloths) have been proven to be around since the second century A.D., napkins have been harder to pinpoint. The rich in Medieval times had tables adorned with beautiful linen and cotton tablecloths while the poor had rough linen or hemp, (these were lesser in quality, but were by no means ugly). Only the absolutely destitute would have used no cloth at all on their table and it would have been seen as a sign of their absolute fall to the bottom of society. So we can assume, the adoption of the tablecloth had become essentially ubiquitous in the Middle Ages. Despite this, we only see the word napkin appear in the 14th century.

The term napkin comes from the French word “nappe”, for tablecloth, with the suffix “kin”, for little. Like most goods, it is likely the napkin began with the very rich and slowly trickled down to the poor.

Prior to the napkin, the table would be laid with the tablecloth and then layered on top would have been a linen towel that would have protected the fine and expensive tablecloth from worst stains. These were referred to as a sanap. They could be highly elaborate with woven designs or plain linen, depending on the rank of the guest they were in front of. By the end of the 15th century, they might be embroidered or laden with lace at the finest tables. Elaborate rituals pertaining to the sanap appear in some places. Though this was mainly within royal circles.

Over time, smaller towels also appeared on the table for individual use. These were smaller than the towels that servants might use or that would be used as a sanap. These might be referred to as a sauvenappe, (an individual sanap) and seemed to be a precursor of the napkin on the medieval table. At first they were laid vertically between guests at the table. They became smaller over time, an etiquette formed around them and they began to be referred to as napkins.

Prior to the dinner each guest would have washed their hands. At a large banquet the hands might have been washed for the guest by servants as they entered the hall or at the table. During the dinner one would have eaten using a knife and a spoon, so it would have been assumed that you would not soil the linens. If you needed to wipe your nose or brow, you were expected to do so on your sleeve.

Now this is not to say that people did not use a napkin-like item prior to the 1300s. There are references to Romans bringing their own cloths to wipe their hands on at banquets. They then used their cloths to wrap up leftovers to take home after the meal. So, napkin like cloths were used at times in the ancient world, It is just the name “napkin” that appeared in the 14th century.

By the 16th century, napkins were a normal part of dining, though the poorer might have a single rough napkin that would be washed and reused over and over. This gave rise to the napkin ring, (but that’s a story for another day). By the 17th century, napkins are a part of the general etiquette of the table.

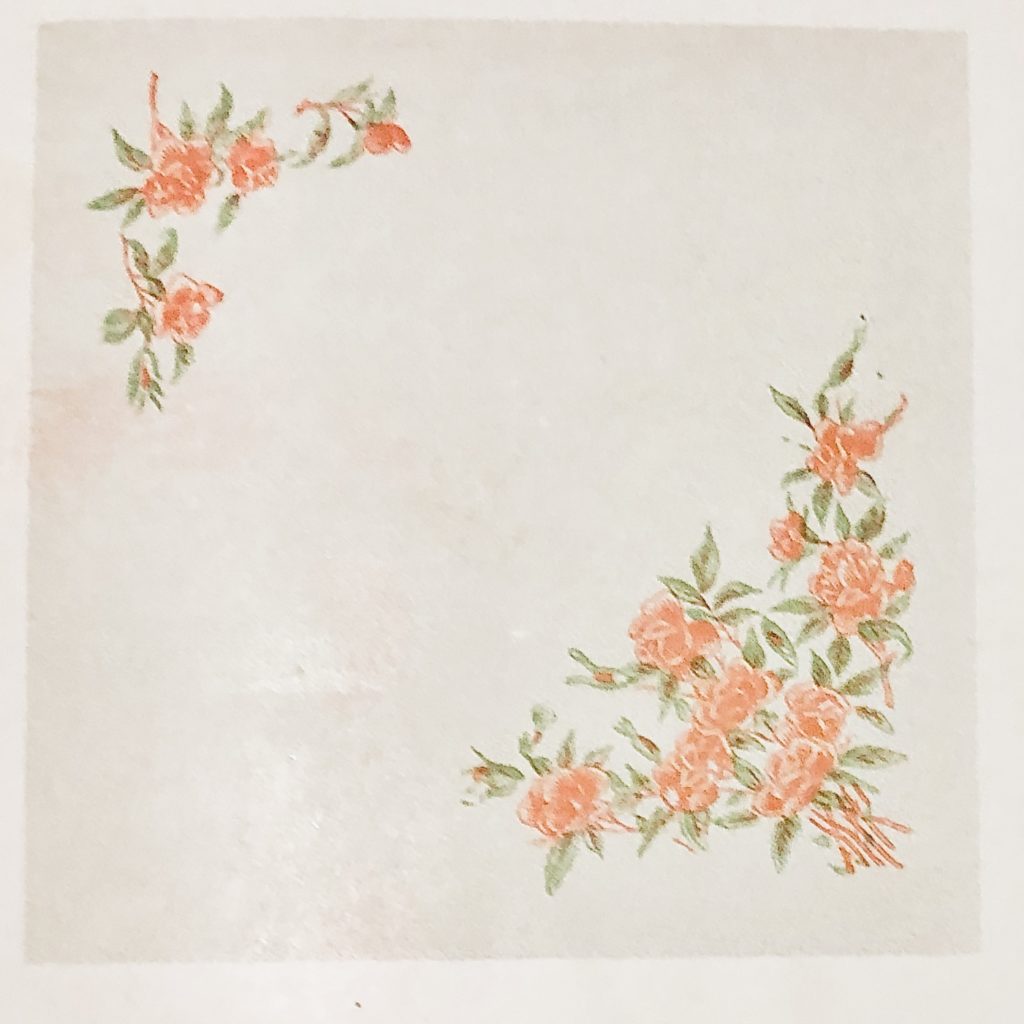

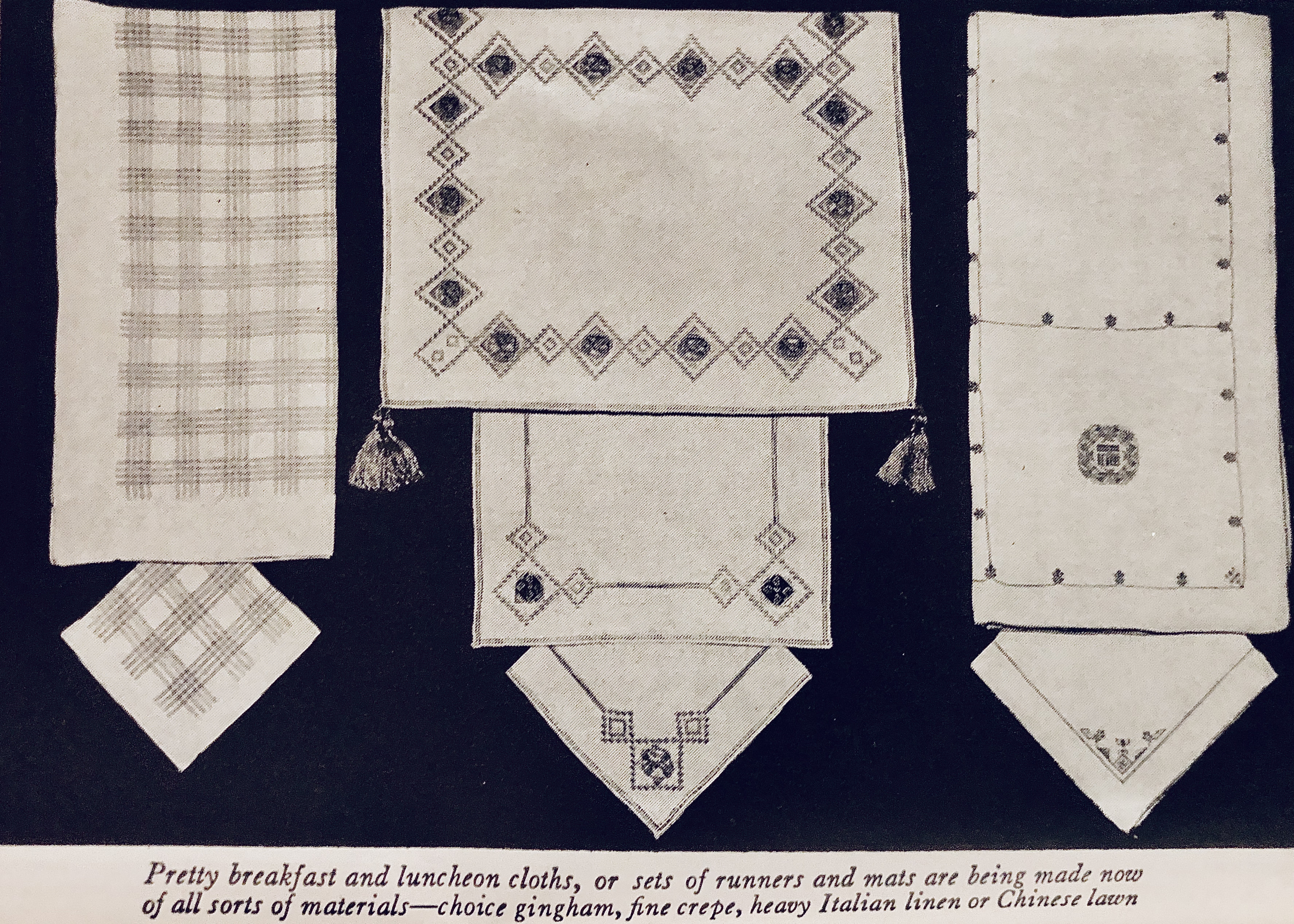

As linens became more ubiquitous, and wealth spread to a larger number of people, table linens began to be made in sets for the fine houses. Tablecloths came with matching napkins and the sets we are familiar with appear. Whole trousseaus of table linens are made and passed down to subsequent generations.

The actual etiquette of the napkin stays fairly similar over time and I will cover it in my next post. Here I’d just like to go over a few of the napkin types that developed.

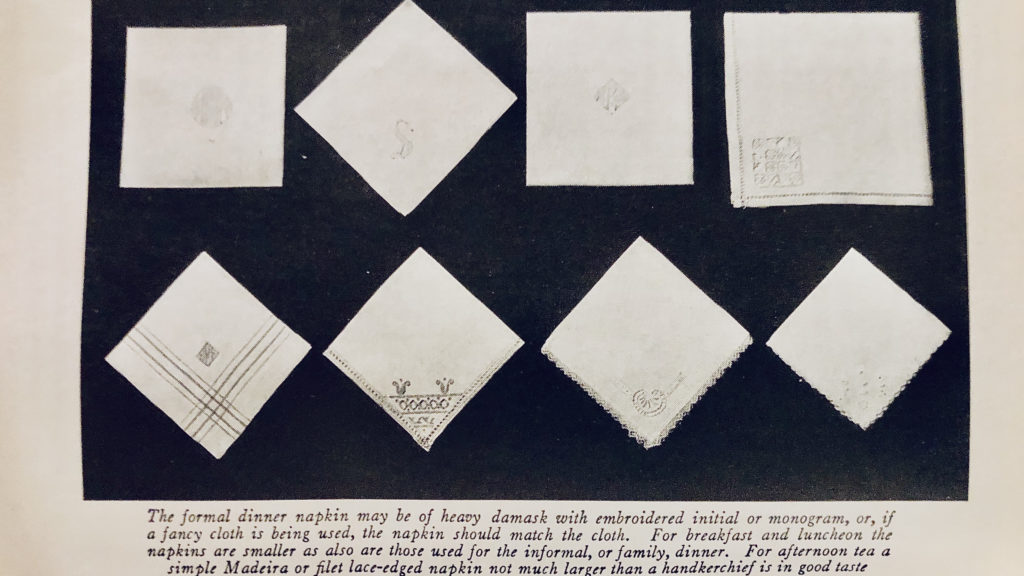

Of course, the O.G. napkin is the dinner napkin. It is large enough to cover the lap more than once. Since it started as a four foot medieval towel, we can understand it’s large size. At first this would have been the only size needed, as meals throughout the day were not thought of as being vastly different. As breakfast became a different meal from the mid-day repast, and dinner became something unlike either of the previous two, napkins were quickly tailored to reflect the character of each meal as it developed. The dinner napkin remained the largest of all the napkins, though it grew smaller over the years until it is the size we have today.

I love finding French trousseau dinner napkins from the turn of the century. they are absolutely huge and are a delight to use.

As soon as napkins appeared on more middling tables, napkin folding became a thing. While fancy folds were mainly a Victorian fad that continued only in restaurants in the the 20th century. How you folded your napkins became a way to show off your cultured nature. There was a revival of the napkin folding fad in the 70s and 80s which reached origami-like heights, but they never quite had the flair of the earlier styles, mostly owing to the smaller size of modern napkins as compared to the endless fabric provided in a Victorian cloth.

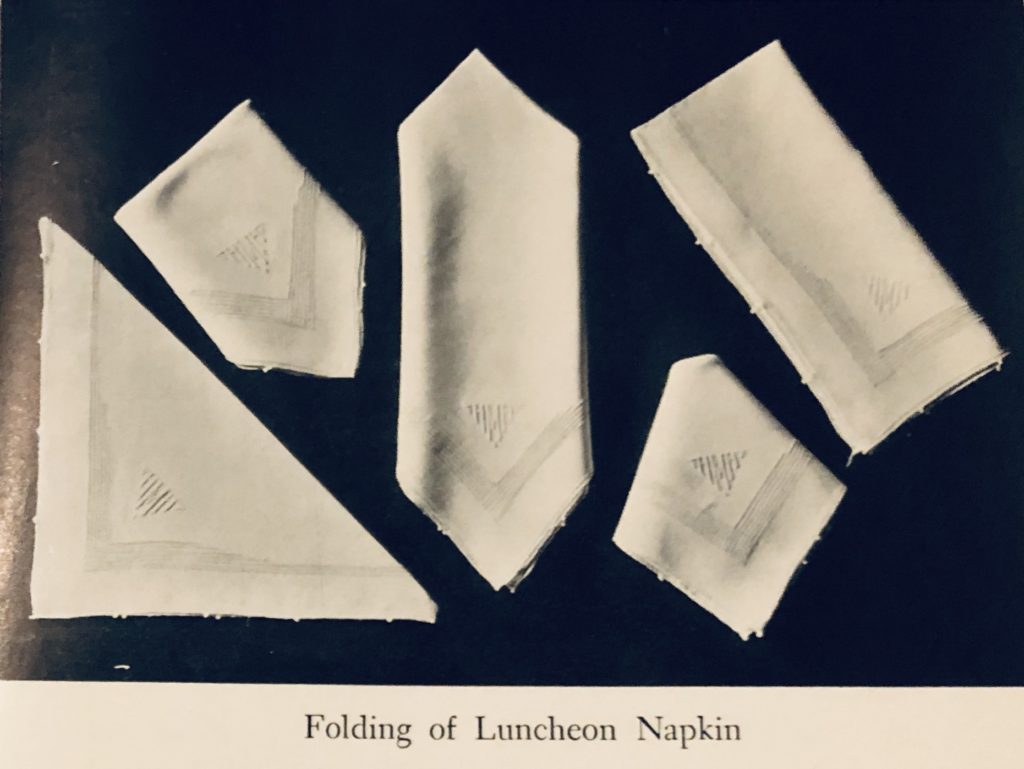

“The dinner napkin should be folded into a rectangle not to exceed in length the diameter of the service plate. For a formal dinner it should be placed in the center of the plate. For a less formal meal with limited service, the napkin should be put at the left of the forks. Luncheon or breakfast napkins may be folded in a triangle and then the two points turned under to form an inverted picket top. Tea napkins may be left in a triangle, if preferred, or in a square if placed within the tea plates. Fancy foldings of napkins are not in good taste and passed into disuse with Victorian customs.”

Let’s Set The Table by Elizabeth Lounsbery, (1938)

The Luncheon napkin is the next in size, followed by the breakfast napkin. By the twenties, luncheon and breakfast napkins can be found in mass market magazines that are basically the same size. That is because linen manufacturers and the magazines in which their ads ran, were loathe to tell regular women that their lunch was not the formal, chichi affair of the upper class women were having. Formal luncheon napkins are somewhere between a dinner napkin and a breakfast or “lunch” napkin.

Formal luncheon napkins were folded in simple elegant ways as befitting a meal that was taken mainly by upperclass women and contained lighter, sophisticated fare.

Tea napkins are smaller still. Folded in tiny squares that are just about the size of a tea cup saucer, they are dainty and made of very thin and elegant fabrics.

Cocktail napkins are unique in that there are several sizes. There are plain squares a little larger than a coaster and there are rectangles that are single ply, and napkins that are folded into rectangles.

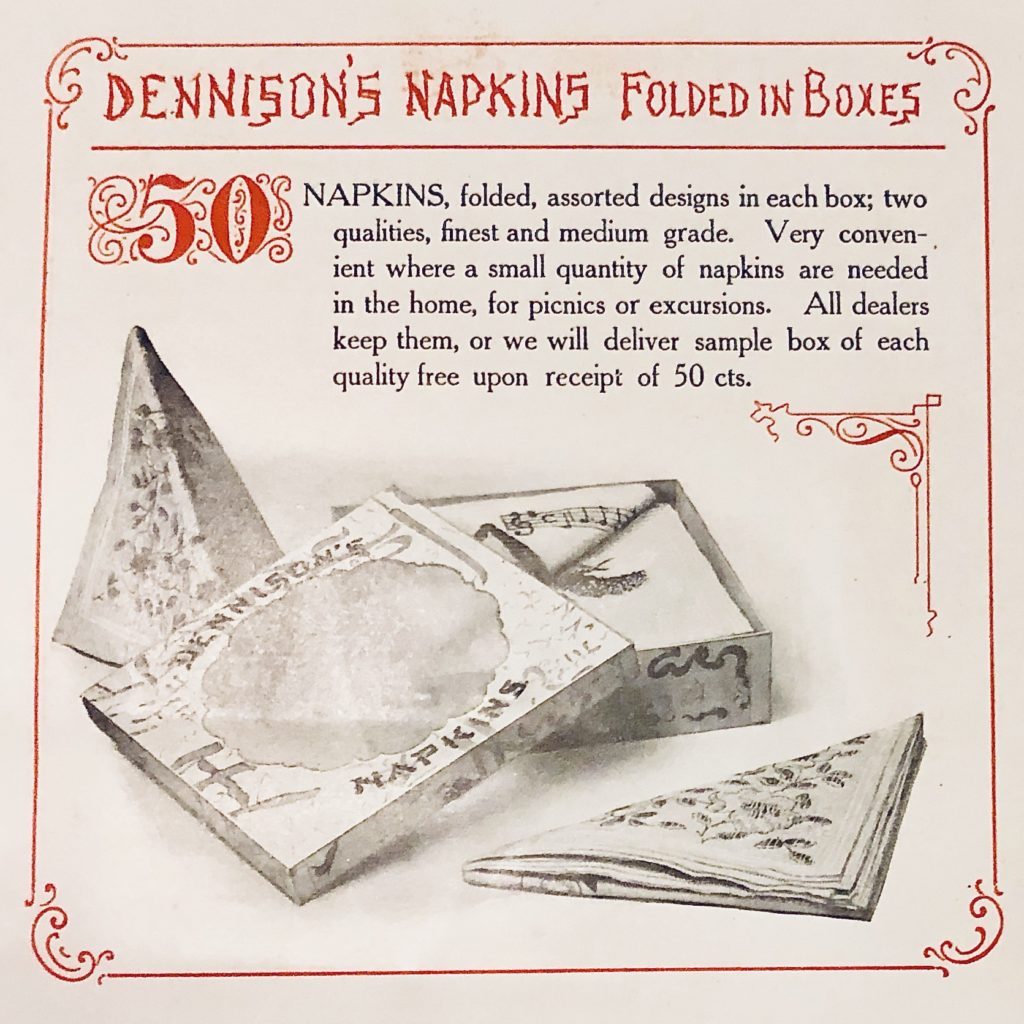

Finally, paper napkins go all the way back to ancient China and were used with tea ceremonies. The modern versions date to the turn of the century, with Dennison – as always- making the most beautiful and popular.

Do you love napkins and tablecloths like I do? Either way, I’m wishing you the best this holiday season and I’m sending you much love.