“A great deal of comfort and satisfaction of a good dinner depends upon the carving. Awkward carving is enough to spoil the appetite of a refined and sensitive person. No matter how well the meats may be cooked, if they are mutilated, torn, and hacked to pieces, or even cut awkwardly, one half of their relish is destroyed by the carver… Besides the annoyance and mortification of bad carving, it is a very extravagant piece of ignorance, as it cases a great waste of meats.”

The Perfect Gentleman; or, Etiquette and Eloquence by A Gentleman, 1860

As discussed in the different types of service, historically carving was a huge responsibility borne by men. It was their moment to shine in front of guests, showing off their gentlemanly grace and knowledge. To carve badly was to embarrass ones self so terribly, one might as well leave society all together and become a grotto hermit.

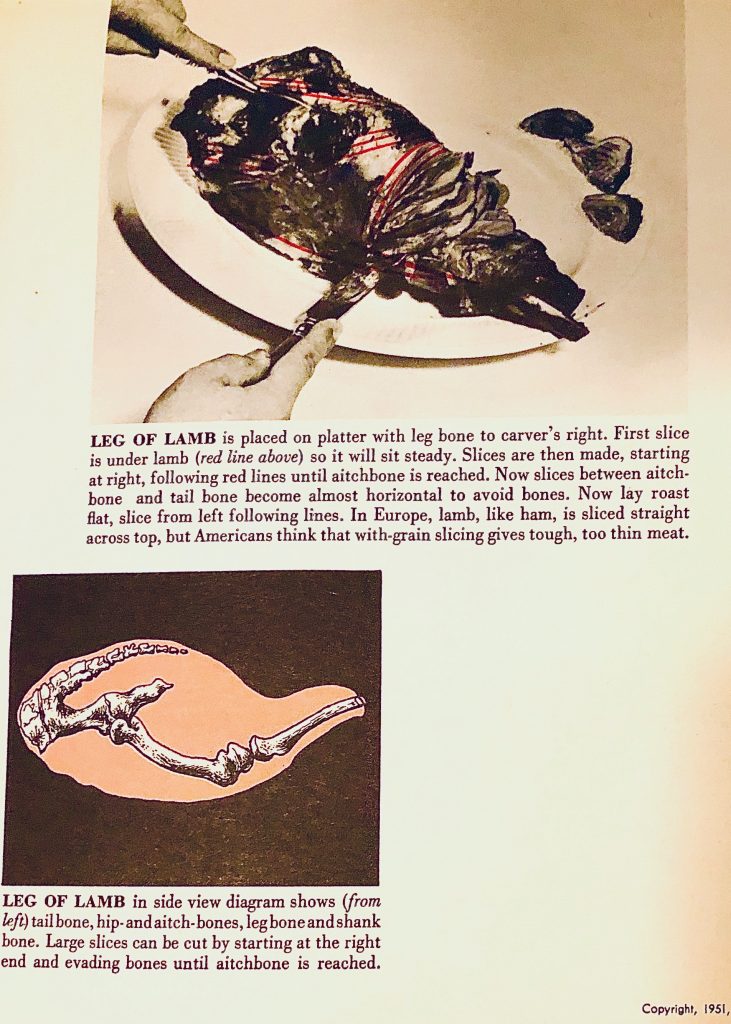

In the same way a great deal of paraphernalia arose around the tea service as it developed into a social test for the lady of the house, so carving had it’s numerous tools and accouterment for the gentleman. Nearly every joint of meat had its own knife and carving fork. Each had a varied length and curvature designed to best aid the host in the carving of each piece of meat. There were also differing kinds of platters, sized to the joint of meat. More interestingly, there were carving cloths, literally cloths that sat under the platter to protect the tablecloth and to prevent the platter from slipping, (these deserve their own post, which I will do later).

As time went on, carving at the table began to be reserved for Sunday dinner or special occasions in most households. Service a la Russe meant that meat was carved in the kitchen and brought out plated. By January 1906, The Boston Cooking-School Magazine was touting that, *gasp* women who served at table should learn how to carve:

“The fact that meat, poultry, game, fish, etc., are now as universally carved on the dining table as formerly argues nothing against the necessity of a knowledge of this subject. Rather, on the contrary it is the best of reasons in favor of the acquisition of skill in practice of this art by all women who take up the calling of a waitress.”

Despite the rise of formal service and ladies learning to carve, amazingly, carving well as social indicator lasted into the 1970’s among certain sets.

So, what is expected of an excellent carve?

“If the carving is to be done at the table, the host must attend to it. He should be prepared with a sharp knife and strong fork. The steel should be banished from the table; it is supposed that he did all the sharpening before dinner was ready, and it certainly is not productive of much pleasure to sit patiently waiting to be served while the host is whetting his knife. He should always sit while carving. He also indicates who is to receive the first plate. The person receiving it should keep it, and pass the plates on as they are designated. When one is to help himself from a dish, he should do so before offering it to a neighbor.”

Twentieth Century Etiquette by George Spiel, (1900)

Despite what George Spiel says, now-a-days carve standing up. Don’t try to carve sitting down as it’s nearly impossible to get the correct view of the meat or make accurate cuts. If you cannot stand, have a low cart set up for that purpose next to your seat.

As someone who’s been pescatarian for a long time, I don’t really have a need to learn how to carve meat. My hubby does partake enthusiastically, but it rarely comes in a quantity which would force him to learn these skills. I suppose for most people the Thanksgiving turkey is the only thing that is still carved at the table. Learning to carve a turkey well is still a useful skill as it really does help show off the flavor and texture to it’s best advantage.

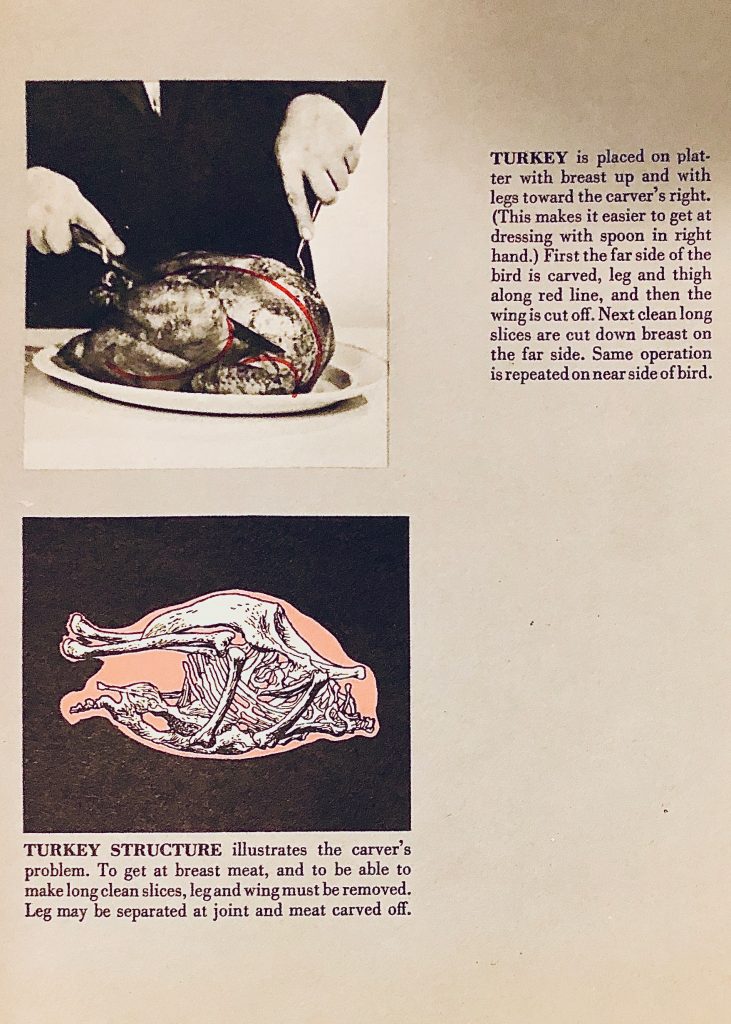

I’ve attached Ida Bailey Allen’s Modern Cookbook from 1924’s turkey carving lessons below:

I hope the diagram above helps when Turkey day rolls around. Sending you hope and love and no dry turkey legs