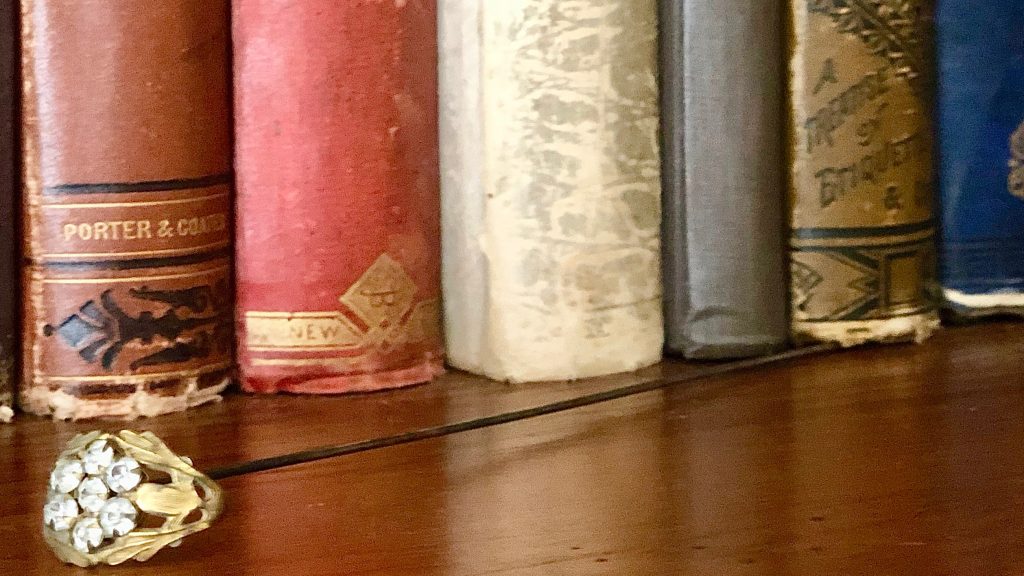

For years my mother wore a large brimmed sun hat out in the garden affixed with a hat pin. She had dozens of hats made of every conceivable type of material and she had many hatpins to match. In my twenties I began wearing hats often, so my mother gave me a couple hatpins. That began a very small, but well-loved and used collection.

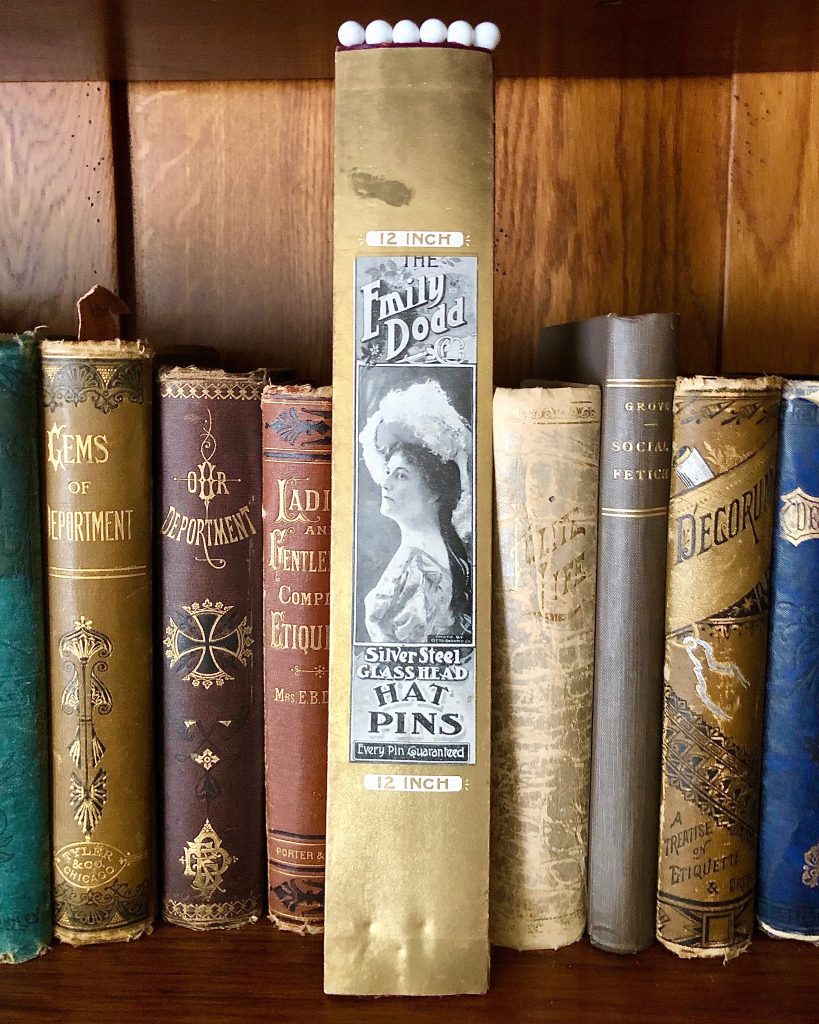

A hatpin is usually from 6-12 inches long, but there are mid-century hat pins that are as short as four inches and Victorian pins as long as 14 inches. The very small pins that are sometimes seen on ebay or etsy labeled as hatpins are likely either scarf pins, lapel pins or decorative pins for hats, which were just accessories. While technically any pin you wear on your hat is a hat pin, what we’re discussing here are the pins used to hold a hat onto a woman’s head. Small decorative hat pins are often referred to as “hat sticks” to delineate them from their more practical cousins.

From what I understand, pins were used to keep head coverings on heads going back as far as the 15th century. Wimples used small pins, but these were more like straight pins for sewing, and pins remained the way you attached a covering to the head for the next few centuries. Well into the 18th century, the most common form of lady’s head covering, the day cap, was still pinned to the hair. Pins that were for the general feminine masses were quite plain and practical, but the wealthy had decorated pins.

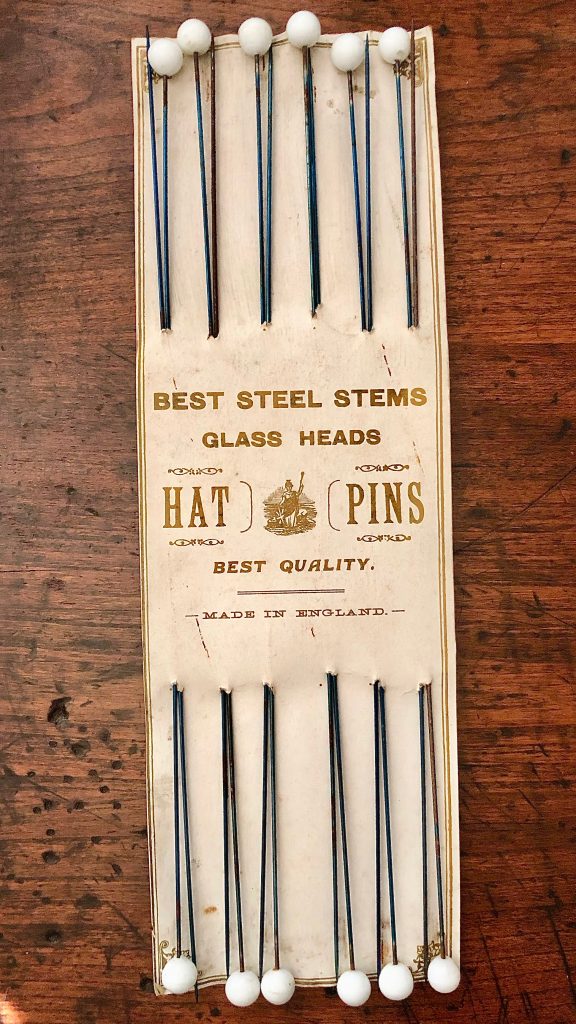

In the early to mid 19th century, pins for hats began to grow longer and were made specifically for the purpose of holding a straw sun hat or bonnet in place. These pins were two to three inches with glass heads, and were usually pinned through the back of the bonnet into the wearer’s bun. Pins were quite expensive as they had to be made by hand.

There is an oft repeated story that by 1820s, the demand for pins was so great that they had to be imported from Europe. Laws were enacted to reduce the number of pin imports, giving only a few days a year that they could be brought into England and sold. Women would save for the day that hat pins went on sale, leading to the phrase, “pin money”. In 1832, pins began to be made by machine and so became more affordable.

Due to changing styles, bonnets in the mid 1800’s began to have ribbon laces which would be tied under the chin allowing them to be worn without a pin, but there remained some styles that required a hat pin. By 1860 parasols replaced the hat as the au fait way to keep the sun off of a woman’s face, allowing hats to get smaller, (that and dress fashions). Styles began to vary with more and more hats removing the ribbon tie and being held in place with pins so they could be tilted forward.

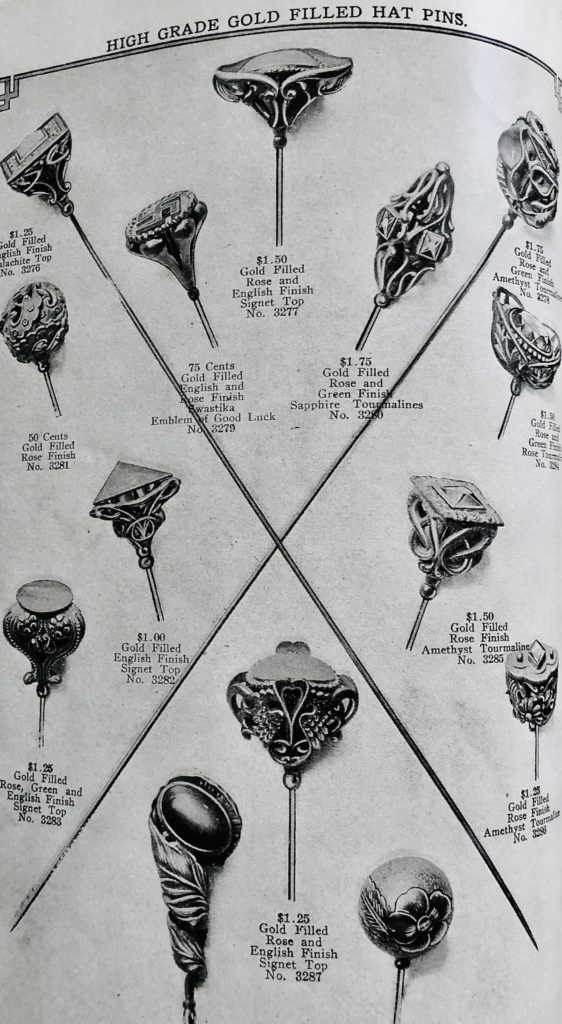

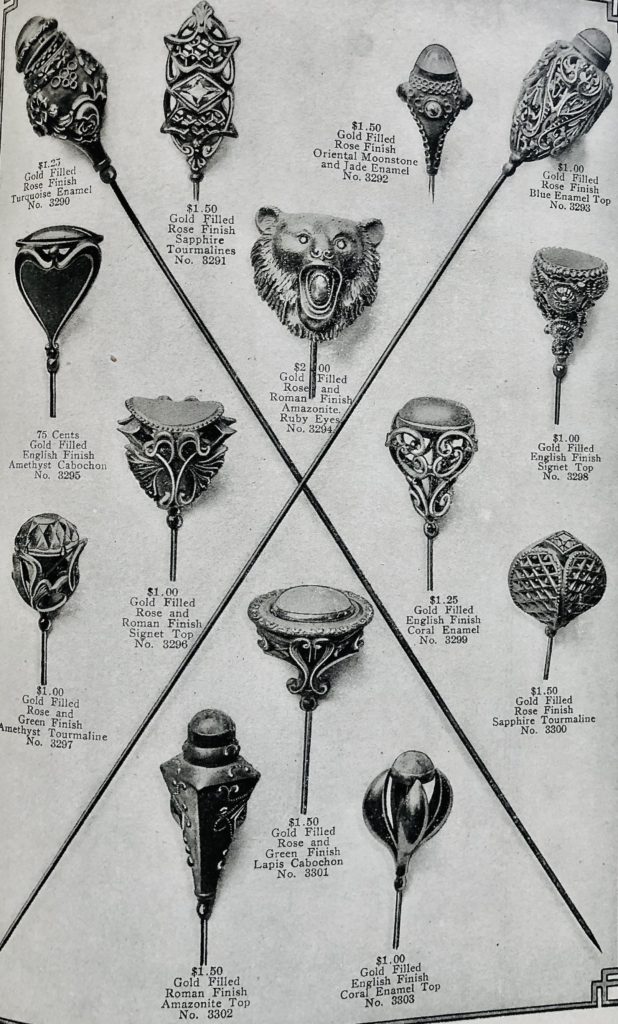

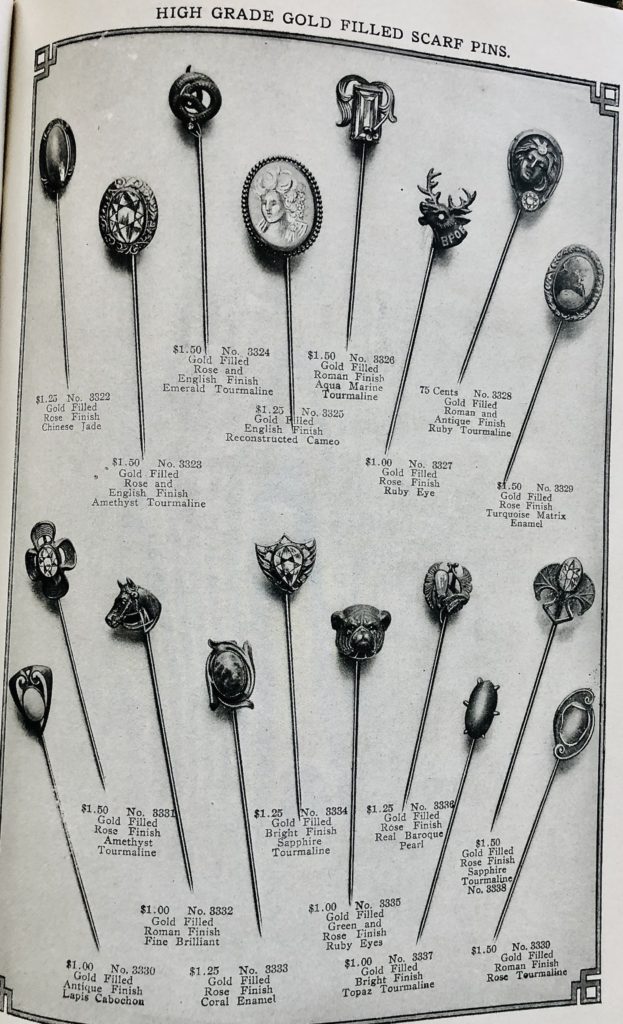

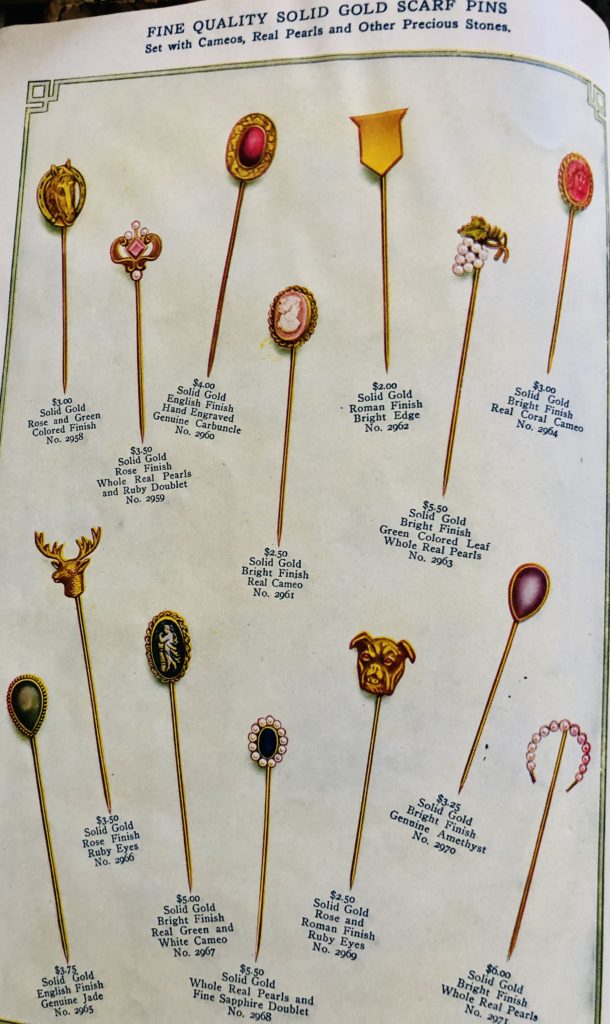

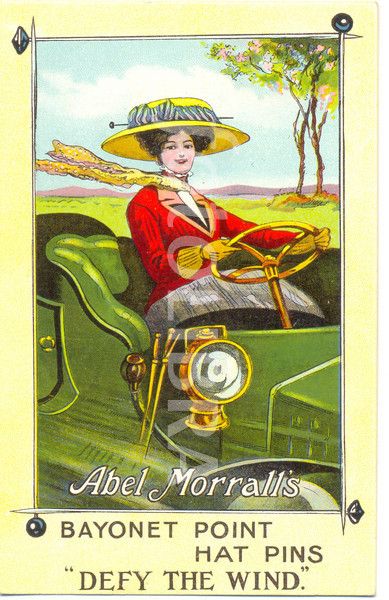

At the turn of the century, hats became larger and larger requiring long hat pins to keep the hat on the head. Celebrities such as Lillie Langtry favored huge hats with feathers, birds and milliners flowers, using long pins to hold the hat in place, rather than ribbons. This is when you’ll see those gorgeous foot long pins with Victorian or Art Nouveau designs. The popularity of these huge accessories lasted mainly from 1890 until 1920, with the peak of 1910, when hatpins reached 10 to 14 inches in length.

Most pins were sold in multiples if plain or in pairs, if decorated. Pins were usually crossed to make sure the hat was secure and rarely would someone have used a single pin to hold the hat in place. Sometime three or four were used with a combination of decorated for the ones that could be readily seen and plain in the places where they would not. Pins could easily become bent, so women were likely to use cheaper glass headed pins to do the heavy lifting.

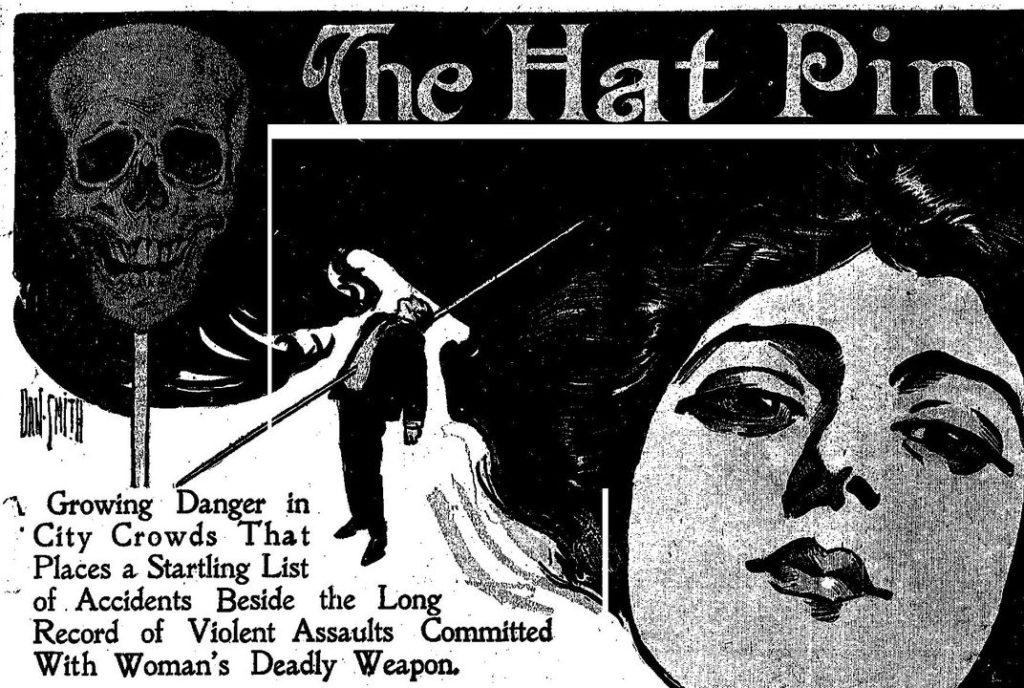

By 1908 there was a backlash to the long hatpin as they were seen as a weapon that a woman could wield to defend herself. Apparently, having ladies defend themselves against mashers was seen as dangerous to the all-male city councils in Britain and the USA, with some places going so far as to outlaw any pin over nine inches. Courts claimed that men were being assaulted by “porcupine” women, one going so far as to claim men had received grievous bodily harm after contracting blood poisoning from a woman’s hatpin. Fines were issued to women who could not give up their long hatpins. This is why you’ll sometimes see turn of the century pins that look as if they have been cut with wire cutters – that’s because they were. It is also why long hatpins are the most prized by hatpin collectors.

In the 20’s cloche hats sat directly on the crown eliminating the need for the hatpin. Also, hair became shorter, which meant there wasn’t much to attach the pin to the hat, so hats adapted. Another nail in the hatpin coffin was the introduction of the bobby pin. Gripping hair pins were invented in Britain during the first world war, they grew in favor as women “bobbed” their hair. Soon women realized these could be used to hold small hats onto the head without needing sharp hairpins.

Hair became longer in the 30’s and hat pins returned, though never as strongly as during the turn of the century. With bobby pins and cheap celluloid combs that could be attached to the hat band, there were too many additional options for holding the chapeau to the noggin. As the century moved on and hats became smaller, the hatpin became shorter. Normally around five or six inches, the pins might now pass through the back or side of the hat, (many hats of this period were worn at a jaunty tilt). Plain pins tended to go the back with decorated pins placed at the side for all to see.

By the end of the second world war, daily hat wearing fell out of favor for year-round. Sun hats and church hats remained. Special occasion hats for riding and funerals. But few of these required a hat pin.

In the sixties the pillbox hat made a strong comeback for hat wearing in general, but only some of these required hat pins. This is where you’d see the four or five inch pin used either in the front or back depending on the placement of the hat and the height of the beehive hairdo. Again, the most elaborate of these hatpins were meant to pin the hair through the front of the hat.

A couple words about collecting: The most valuable hatpins are by jewelry designers who dabbled in hatpins, including Louis Comfort Tiffany, (signed as LCT), Peter Faberge, (signed as Faberge in Cyrillic though sometimes unsigned) and Rene Lalique, (signed as R.L.). Next down are those made by lesser jewelers and silversmiths. You’ll find that these are signed or stamped on the underside of the head.

Be careful when collecting hatpins, they are quite easy to fake. I can’t really advise buying hatpins over the internet unless you have really good pictures and a really reputable dealer. Look for signs the pin head has been soldered onto the shank. That can be the sign of a fake or at the very least, a repair. Everything from buttons to shoe chips to brooches have been converted into hat pins.

Etsy is horrible at mis-labeling the era on hat pins. If a pin is 4 ½ inches, it’s not Victorian, (unless they tell you that it’s been cut or damaged). Ornate hatpins from the 1890’s to the 1910’s will likely be ten to twelve inches. Pins worn by lower and middle class women might be as short as six inches. Pins from the thirties tend to be made of less expensive materials due to the depression. Cellulose, feather, wood and plastic hair pins appeared and were often around five inches. The second world war meant that metal was sent to the war effort, so this trend continued. Highly decorated pins with lightweight plastics that are four to five inches are most likely mid century. In the eighties there was a victorian revival and hatpins made a comeback. There are reproductions of 10-12 inch hatpins from this period. You just have to get to know your materials as they are usually made from cheaper quality metals, modern glass and/or plastic.

If you want to read more, Hat Pins by Eve Eckstein and June Firkins is a good start, I used it to fact check much of this post.