“The time has come,” the walrus said, “to talk of many things: Of shoes and ships – and sealing wax – of cabbages and kings”

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, (1886)

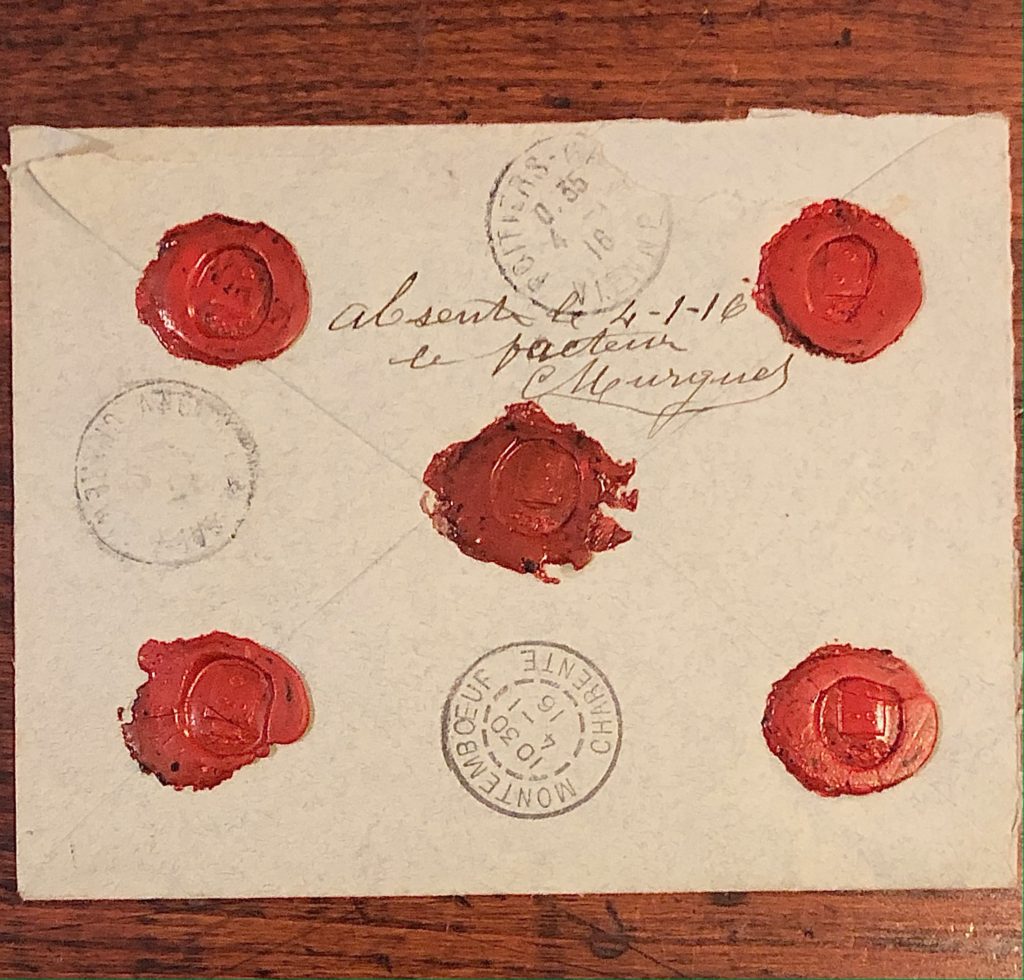

When I was a kid my dad read Alice in Wonderland out loud to me. At the point that he came to the Walrus’ lines above, I stopped him, confused. How did the wax get on the ceiling? I had seen beautiful ceiling tiles and rosettes at the Getty Museum, so I asked, are those made of ceiling wax? My dad thought this was hilarious. He explained that this was a different type of seal. After some hunting, he found a book in his collection that contained photographs of old letters sealed with insignia. We poured over them and I was hooked. It was all so romantic, seals protecting love letters for only the loved one’s eyes, spies trying to retrieve messages without breaking a seal. It began a love affair with seals and sealing wax that hasn’t let up to this day.

Using sealing wax to close letters has been practiced since the Middle Ages. That was the period that sealing wax actually contained wax, (amongst other things). It was very soft, could be peeled off, melted on a hot day and generally wasn’t very good. Early letters didn’t have envelopes. You just folded them and then used wax or metal crimps to hold the letter shut. So even soft and melty wax was still useful.

Sealing wax was also used in place of a signature on documents at the time and can be seen on everything from court documents to the Magna Carta, (it was sealed, not signed).

In the 1500s, shellac meant seals were harder and truly served the purpose of keeping prying eyes out. Made of the resin excreted by the female lac bug, shellac is tough, water resistant and shiny. To this, color and rosin were added to make a durable and attractive sealing wax. Rosin is a resin made from pine or conifer plants. It adds density and a glass like quality when hard. This gives shellac seals that satisfying crunch when you break them.

As time wore on, sealing wax etiquette was codified and added into the etiquette of letter writing and stationary. Everything from how you folded your letter to the placement of the address in response to the seal was set. The color you chose to seal your letter was also important. Blue and Green wax was used for informal letters. Red was extremely formal and used for legal, military and governmental documents. Black was for mourning and death notices only.

As the 19th century approached, innovations in wax meant that new, finer waxes were less likely to shatter during mail delivery. Sealing wafers were also developed in the early 1800s, which did away with wax altogether. It allowed for neater mail delivery, but it was considered less attractive and often in poor taste to use them. For a formal letter or a letter to an important person, sealing wax was still the proper thing to use. By the late Victorian period, wafers had disappeared and wax remained.

“Private letters should always be sealed with wax, in color dark green or red. Black is used for mourning. In sealing a letter, be careful to make a neat effect, and not to smear the wax all over the envelope. The seal is then stamped with your monogram, or, if you insist upon it, with your crest, but never with your coat of arms.”

The Complete Bachelor by the Author of the “As seen by him” Papers, (1896)

By the turn of the century, seals were mostly seen on formal documents, such as deeds and indenture agreements. Certainly, as soon as the mechanical mail sorter appeared, sealing wax’s fate was sealed, (sorry, I couldn’t help it). Sealing wax gummed up machines, and so post offices stopped accepting wax sealed letters.

Now, sealing wax has made a bit of a come back, if mainly in crafty circles. Modern sealing wax is flexible and can be sent in the mail, though you should put it inside an additional envelope, as wax still jams up the machines.

If you’re interested in how letters were folded prior to the envelope, Jana Dambrogio of MIT has an incredible YouTube channel called LetterLocking that shows how letters were folded in history. Letter locking is the study of folding and securing a piece of paper to become it’s own envelope. I’m obsessed.

In these alone-times, letters have taken on even more importance. Yes, we have email and social media, but the personal nature of a letter that can be held, read and re-read seems dear to me now. If you’re far away from me and you want a pen-pal, let me know, I’m in the market.

With most sincere fond wishes. Much love, Cheri